Earlier this month I visited the campus of Harvard University to see archival file folders located in the basement of the Frances Loeb Library at the renowned Harvard Graduate School of Design. For nearly 70 years modernistic architectural design plans for high-rise hotels and casinos have been filed under “Block Island Design Project, 1952.” All these architectural designs, drawings and photographs of models stemmed from the following design question, “Suppose we bought all of Block Island, razed it with bulldozers and turned it over to you, what would you do to make it the most modern, complete vacation center in the world?”

Over the past six months of our work digitizing the Historical Society’s archival collection (funded by the Annenberg Foundation) I have found crumbs hinting at this intriguing 1951-1952 Harvard study centered on Block Island. Newspaper clippings showed models of the familiar Block Island landscape with modernist building designs including casinos, dog tracks and high-rise hotels. As a child of the 1970s, I must admit these radical modernistic plans made me think of my time at preschool watching reruns of the animated sitcom “The Jetsons.” As this collection was not digitized, I needed to visit the archives in person.

Hibernation

Some historical perspective is in order to truly understand the boldness of these designs. In 1952 Block Island was in what I refer to as a hibernation. Many of the grand hotels were vacant or underutilized. For example, the massive,

decaying Ocean View Hotel, which in its prime had entertained President Ulysses S. Grant, in 1947 sold at auction for just $11,000. In the 1950s someone my age would drive past these unpainted and deteriorating buildings and

remember the grandeur of multi-course meals served by an army of staff that included the delivery of finger bowls garnished with lemon between courses.

The trifecta of economic downturns, the Great Depression, the Hurricane of 1938 and World War II, all greatly reduced the role of tourism on Block Island. We know today that Block Island would be “rediscovered” as a tourist destination, but that was not clear to those residents in the early 1950s. Were these fading buildings a sign of hibernation? Or just a part of a slow and continuous decline since the heyday of the Gay Nineties?

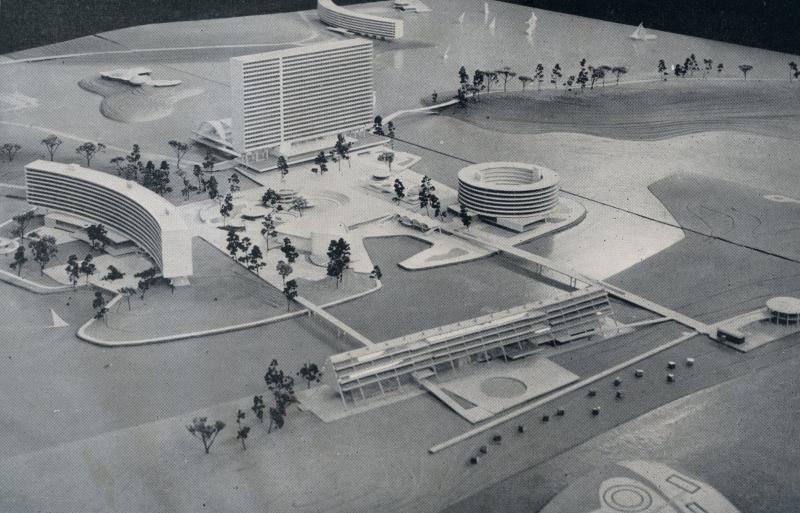

The New York Times, in March 1952, ran an article on the Block Island design projects under the title “Idealizing a Resort: Harvard Design Students Try Bringing the Old Swimming Hole Up to Date.” Ninety Harvard graduate students commenced this architectural design project with extensive research, including visiting the island in person, talking with the local residents and even photographing contours of the island from the sky. All this research aimed for the study to yield a range of unique architectural and landscape plans for a proposed “streamlined” Block Island, which included casinos, a horse track, shopping centers and country club (with a golf course, of course) and a conveniently adjacent yacht club. All these diverse plans encapsulated the overarching goal of transforming Block Island into a “stately pleasure dome.” One newspaper, in summing up these many proposed Block Island designs wrote, “Chromium, glass, flaring aluminum roofs, sweeping columns and pavilions filled with perfume and soft music.”

The students were led by the famed German-American architect Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus School of architecture, and along with such architects as Frank Lloyd Wright, he is considered a founding father of the modernist architectural tradition. Two of Gropius’s building designs that can be seen today include the 59-story Pan-Am Building on Park Avenue in midtown Manhattan and the two 26-story offset towers in downtown Boston known as the John F. Kennedy Federal Building.

American assembly lines won World War II. Now, rather than making Sherman tanks, factories produced consumer products like Chevys and refrigerators. This consumer culture mindset of the early 1950s was all about production and potential. Block Island of 1952, from the point of view of this mindset, was lacking in both. One newspaper clipping I found described Block Island with, “Humble fishermen’s dwellings house the majority of the thousand-odd population, and the town’s business is conducted in a small one-room frame building. There also are a six-room brick schoolhouse, an infrequently used hotel, and ancient movie theater, a number of antique automobiles.” These comments were not so much highbrow cultural criticism as opposed to highlighting the lack of promise. Before the modern environmental movement commenced with Rachel Carson publishing “Silent Spring,” open space was underutilized space. In the 1950s Disneyland would open on cleared former orange groves in California and Phoenix’s population would explode thanks to air conditioning.

The pace of American life was accelerating and impacted how people dressed, traveled and interacted with one another. This was a time when airports were constructed with observation decks for people to just watch take offs and landings. Small pockets of America however, like Block Island, and such locations out west like Telluride, Colorado, escaped many of these postwar features like national hotel chains and neon signage. As a result, such locales began to stand out and function as a place apart. One travel writer in 1947, after a visit to Block Island wrote, “Islands breed individualists, and the inhabitants of this tight light isle are all definite personalities, with none of the colorless anonymity that cloaks so many city dwellers.” This doesn’t mean that island residents felt no threat from these outside, mainstreaming forces. One resident fearfully wrote, “The time may come when it will be impossible to tell a Block Islander from any other citizens of these United States. That time is not yet come and those of us who love this island hope that it will never come.”

Orchidry

The Harvard plan that received the most attention was the mile-long arc pyramid hotel running south to north along Crescent Beach. For perspective, if using the U.S. Capitol Building for reference you would need seven of these structures end to end to equate to the proposed length of this hotel on Crescent Beach. The planned structure was so much more than just a hotel that could house 10,000 guests nightly, but also included shops, tennis courts,

ballrooms, playgrounds for children, theaters and an orchidry. The latter term described a futuristic combination of tropical greenhouse and cocktail lounge that would allow patrons to drink French wine and see majestic views of both the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Salt Pond. A contemporary periodical hinted at the impact of this state-of-the-art orchidry on the longstanding watering holes on Block Island. It read, “The Yellow Kittens and other well-known island oases would find themselves competing with a group of scientifically located, functionally designed chrome and glass cocktail lounges.”

The west side of the island also attracted the attention of the students, in particular Franklin Swamp. Detailed plans from one team of students called for the water feature to be drained, dredged and refilled. The manmade islands within this newly refitted water feature would include “small” hotels accommodating 500 guests each. Stone walkways between the islands would allow guest access to nearby beaches, cocktail bars and theater. Racing enthusiasts would have loved the streamlined Franklin Swamp as the design plans incorporated a combination horse and dog trac accessible by foot (the center of the horse track would have been at the intersection of Cooneymus and West Side Roads.) Gambling of course, would be facilitated at this track with plenty of eating and drinking options. I propose that these plans were in fact more radical for the early 1950s than today when one considers the context. Rhode Island itself was a decade away from the first McDonald’s franchise opening up, which took place in 1962 in Warwick. The ubiquitous Dunkin Donuts of the modern Rhode Island landscape, existed, but just had one location, Quincy, Massachusetts, where the original store opened in 1950. Interstate 95 crossing the state, the Newport Bridge, T.F. Green airport, were all years in the future. If these hypothetical plans were carried out it came with a price tag of $50,000,000 USD. This, at a time when only one in three American families owned a television, the minimum wage was 75 cents an hour and a gallon of gasoline averaged 27 cents.

Martha Ball, in an interview with the Historical Society in 2000 noted a unique challenge to those seeking to save open space on Block Island. Failures stand out more sharply than the victories. Meaning, with the victories of preserving open space, there is only nature. There is nothing to see compared to a failure that resulted in a massive structure of unsurpassed opulence.

I thought about this quote when in the basement archives of the Frances Loeb Library at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. While it is easy to say, “Oh these are just plans, they would never have occurred,” I would beg to differ when one considers what transpired in Atlantic City in 1977 with the legalization of gambling. Or, of the Foxwoods Casino in Ledyard, Connecticut, which commenced in 1986 with a single bingo game and now is six casinos covering an area of 9,000,000 square feet with over 5,000 slot machines. While things are not perfect on Block Island during the peak of season, I am thankful the tempting fruit of legalized gambling was never plucked on Block Island.

The reaction of the year-round residents to the Harvard plans is nothing short of priceless, and a subsequent article will be devoted to this topic. However, I will conclude with a nugget of wisdom from Francis B. White, painting contractor and lifelong island resident, when he pondered the construction of a horse track on the island. In reaction he stated, “The island is bad enough with automobiles. Horses for the island would be fine if they were hitched

to a surrey like in the good old days before the auto came.”