From thousands of acres of farmlands to thousands of places of worship and from shiny commercial enclaves in urban centers to flowing fields in swelling suburbs, a newly released list shows The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints owns U.S. properties valued at nearly $16 billion and ranks the Utah-based faith among the nation’s top private landholders.

It may be no surprise that a growing pioneer-era church with millions of members — and devoted to acquiring land, cultivating crops, erecting temples and building Zion — would today hold vast expanses of property.

Still, the sheer scope of church-held domestic real estate yields mind-stretching numbers. And the findings emerge when many Latter-day Saints and church observers are already agog at other recently reported multibillion-dollar figures associated with the faith’s wealth.

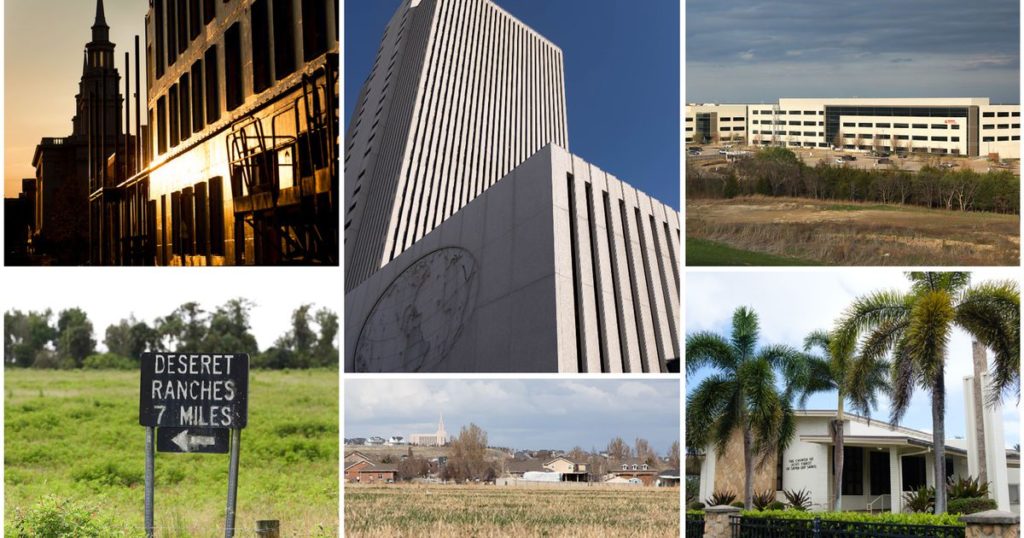

This latest cache of data — captured in 2020 and released Tuesday by the Truth & Transparency Foundation (formerly known as MormonLeaks) — reveals an immense 15,963-parcel collection of 1.7 million acres held by identified LDS Church firms. While the list is not complete, it nonetheless shows church lands in every state, just about every sizable metropolitan area and big blankets of territory in between.

[You can search for U.S. properties owned by the LDS Church here. Find properties on a map here.]

Found in the church’s portfolio — along with the expected meetinghouses and temples — are office towers, shopping centers, residential skyscrapers, cattle ranches and high-mountain timberlands worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

The faith is now Florida’s biggest landowner, controlling well above 2% of its landmass, including an enormous collection of pasturelands outside resort-rich Orlando called Deseret Ranches and a recently acquired expanse of hundreds of thousands of forested acres in the Panhandle.

(John Raoux | AP) Cowboys herd cattle from one pasture to another at the LDS Church-owned Deseret Ranch in Deseret Ranch, Fla., in 2015.

Church companies such as Property Reserve, Suburban Land Reserve and Farmland Reserve are sitting on large tracts of developable land in a host of American suburbs. These holdings are heavy in metro regions throughout the rapidly growing South and West — just as the U.S. economy is primed with high demand for new homebuilding.

Even this partial portfolio would make the church — with nearly 7 million members nationally and more than 16.6 million worldwide — the fifth largest private landowner in the U.S., according to The Land Report, which tracks holdings among some of the nation’s wealthiest families.

The report shows only California-based Sierra Pacific Industries, owned by a third-generation family with 2.3 million timberland acres; businessman and philanthropist John Malone, who led cable giant Tele-Communications Inc. (2.2 million acres); the Pacific Northwest’s Reed family (2.1 million acres); and CNN founder and media tycoon Ted Turner (2 million acres) have more.

Church holdings top $100 million in assessed valuation in at least 15 major urban centers — based on 2019 tax data — and exceed $25 million in at least 66 cities.

The data was built from a digital sifting of public property records in all U.S. counties. Truth & Transparency drew on a private, subscription-based commercial real estate data and research firm, Reonomy, whose algorithms correlated the records with thousands of other data points to confirm their ownership.

The foundation announced Monday it was ceasing operations, making the property investigation its last project published under the Truth & Transparency name.

“Like everyone, our lives have changed greatly in the past two years,” foundation co-founders Ryan Mecham and Ethan Gregory Dodge wrote in an account accompanying the release on the group’s website, “and we both feel this is the best decision moving forward for our personal and family lives.”

In response to a Salt Lake Tribune query, church spokesperson Doug Andersen said that “real estate holdings are used to fulfill the religious mission” of the faith.

“This includes,” he added, “providing for the welfare and humanitarian operations of the church; providing for religious worship (chapels, temples, missionary offices, educational centers and efforts and more); and preserving a sacred religious site or its surroundings and enhancing the character of the local community.”

Andersen said the global church follows the “Savior’s teaching that we should be ‘good and faithful’ stewards over the sacred donations that come from his followers (Matthew 25:14-21). This includes purchasing, holding and operating farms and other real estate properties as investments as a part of the church’s reserves.”

How much land and what it’s worth

(Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune) Property owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in downtown Salt Lake City, clockwise from top left: The City Creek Center mall; an office building on Social Hall Avenue; the Church Office Building; and the Brigham Apartments on South Temple.

Taken together, church properties on the Truth & Transparency list would cover about 1.3 million football fields, spread over at least 3,120 cities and towns and sparser rural areas in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

The portfolio has a value of $11.8 billion set by county assessors for tax purposes, McKnight said, but with a market value of $15.8 billion, established by Reonomy’s algorithms. And even that all but certainly lowballs the actual value of all the U.S. land the church owns.

The Tribune found several high-dollar church properties missing from the database, for instance, including some held under other church companies. And this tally excludes huge church landholdings internationally.

Patrick Mason, head of Mormon history and culture at Utah State University in Logan, called the $15.8 billion total a “staggering sum.”

“It helps us appreciate just how remarkably successful the church has been over the past half-century or more,” Mason said, “in transforming itself from a local, Intermountain West-based sectarian religion to one that really is pervasive throughout the United States.”

In terms of acreage, the properties listed — though likely undercounted and undervalued — exceed several estimates by scholars of the faith’s domestic landownership.

Properties extend far beyond chapels and temples

(The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) Renovations to the temple in Mesa, Ariz., included a new visitors’ center and residential/retail construction owned by the church, similar to Salt Lake City’s City Creek Center, though on a smaller scale.

The list expands outward from a backbone of an estimated $8.3 billion in religious sites, ranging from thousands of utilitarian meetinghouses to scores of architecturally striking temples and adjoining spaces adorning city centers and ritzy suburbs.

There also are hundreds of exhibition halls, libraries, museums, schools, family centers and other sites ancillary to the faith.

Frequently clustered around Latter-day Saint temples, the portfolio’s most lucrative commercial holdings feature in the country’s top downtown cores. The church’s office, residential and retail towers rise up and down the East and West coasts. They also emanate from Utah into neighboring states — all part of the so-called Jell-O Belt — and across the U.S. interior.

Examples in Philadelphia (including a 30-plus-story apartment tower across the street from a temple), Chicago (a 40-story residential tower in the South Loop) and other cities offer distinct echoes of the mixed-use development model found at City Creek Center, with its stores, restaurants, condominiums and apartments near Salt Lake City’s Temple Square.

One church-backed project in the Mormon-settled suburb of Mesa, Ariz., could be dubbed City Creek South. It has all but replicated that urban in-fill approach, though on a smaller scale, with 12,500 square feet of ground-floor retail outlets, 240 apartments, 12 town homes, 70,000 square feet of landscaped open space and underground parking built around a renovated Mesa Temple served by light rail.

The makeover has revived an area in desperate need of a boost.

“There was a time where the heartbeat was difficult to find in downtown Mesa,” Mayor John Giles said last fall in a church news release. “…[The church’s] decision to invest in our downtown sent a great signal to the rest of the smart investors that said, ‘Well, gee, if they’re doing it, that’s a sign that it’s got potential.’”

Andersen, the church spokesperson, pointed to the Philadelphia and Mesa projects as examples of the faith’s investments “enhancing the character” of a community.

Lucrative office buildings also abound, including a $106 million complex in the Dallas Fort-Worth area that one of the church’s property arms leases to aerospace and defense firm Raytheon. The church also owns a complex in Austin and another in Minnetonka, Minn., both valued at over $40 million.

(Liesbeth Powers | Special to The Tribune) An office complex in Richardson, Texas, owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, photographed on March 30, 2022.

The list contains up to $696 million or more in residential lands, vacant spaces and other swaths in America’s suburbs, much of it poised for development. The database details a total of at least 181,000 acres in empty residential lands and vacant farmlands in larger and rapidly growing metro areas, places such as Tulsa, Okla.; Kansas City, Mo.; Lafayette, Ind.; Albany, Ga.; and Modesto, Calif. (where the church just announced plans to build a temple).

Plenty of farms crop up in church holdings

Perhaps the most impressive of the church’s lands in terms of acreage are some of its gargantuan food-production and cattle-growing operations, run by its farming subsidiaries, Farmland Reserve and AgReserve.

The database documents farm holdings worth at least $2.3 billion, with notably huge sections of it in Nebraska, rural Montana, Florida, Texas and Utah. Farms, ranches, pastures, orchards and other agricultural lands under church ownership stretch horizon to horizon, with tens of thousands of contiguous acres in many cases.

(John Raoux | AP) A sign for the LDS Church-owned Deseret Ranch offices in Deseret Ranch, Fla., in 2015.

A church subsidiary called AgriNorthwest recently outbid a Bill Gates-owned company with an offer of $209 million to buy Easterday ranch properties in eastern Washington out of bankruptcy proceedings. The working ranch included 12,000 acres of potato, onion and cattle lands as well as valuable water rights.

Based on acreage, agriculture makes the church one of the nation’s largest holders of farmland and ranchland — and the country’s largest nut producer, centered on expansive orchards in Northern California. Its cattle operations brand it among the largest beef suppliers to the McDonald’s restaurant chain.

Though some of the food is sold commercially, it’s unknown just how much of the production is income-generating and how much goes toward the church’s far-reaching humanitarian operations and support for members worldwide. Nor is it clear what income is generated by its commercial properties, including substantial leasing income from office and retail tenants.

What else does the church own?

(J. Matt | Special to The Tribune) Property owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Laie, Hawaii, clockwise from top: The Laie Hawaii Temple; the campus of BYU-Hawaii; a shopping center on Kamehameha Highway; and the Polynesian Cultural Center.

Between city jewels, lands for future homes and agricultural empires, the church appears to have a version of just about every other kind of parcel in between.

Its holdings include acres assessed for use as island resorts, hotels, airports, golf courses, amusement parks, theaters, vineyards, warehouses, truck stations, funeral homes, health clubs, mines and cemeteries. There are even millions of dollars in thousands of tiny odd-shaped parcels and other bits and pieces known as easements.

The continental breadth of the faith’s holdings is also astounding.

Its Eastern holdings sweep down into Key West on the southernmost tip of Florida — one of three states (besides Utah and California) on this list with at least $1 billion in church-owned land.

Head northward to the farthest tip of Maine, a state where the church holdings surpass $24 million, and you’ll find a three-acre lot and meetinghouse in the far northern border city of Caribou in Aroostook County.

Outside the contiguous U.S., the tally confirms the lucrative value of church properties in Honolulu as well as around Brigham Young University-Hawaii and the Polynesian Cultural Center, both in Laie. Last year, a church subsidiary bought a 200-room Residence Inn by Marriott on Maui for nearly $100 million.

(J. Matt | Special to The Tribune) A Courtyard Marriott hotel in Laie, Hawaii, that is owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, photographed Friday, April 1, 2022.

In Alaska, the faith owns several multimillion-dollar properties in Anchorage and even a small lot in the North Pole, a town in the Fairbanks North Star Borough.

Conversely, Utah is the equivalent of a Latter-day Saint Vatican, at least in terms of property ownership.

The church’s legacy in the Beehive State has given it somewhere around $5.3 billion — yes, a third of the overall value in the database — in land across the state, including at least $3 billion in property stretching from Ogden to Provo.

Does the church pay taxes on all this land?

(Rachel Rydalch | The Salt Lake Tribune) Property owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Riverton, clockwise from left: Undeveloped land looking toward the Oquirrh Mountain Temple; an office complex; and a Deseret Industries store.

Church authorities have consistently said that their for-profit real estate and other business endeavors pay the required taxes.

The vast majority of church properties in the new database are categorized by county assessors for worship, making them tax-exempt.

Add to that a host of other special-purpose properties, dedicated public spaces, vacant areas and other kinds of low-producing acreage, and nearly $8.5 billion total assessed value in the church land portfolio potentially would qualify for lower local property taxes, not including farmlands.

Not so for $2.8 billion or so labeled on this list assessed as commercial properties. And it’s unclear from these records how income from these church-owned properties might be taxed.

While the governing First Presidency has said the church takes “seriously the responsibility to care for the tithes and donations received from members” and has insisted it “complies with all applicable law governing our donations, investments, taxes and reserves,” the faith discloses little about its extensive financial activities.

That bothers some members and nonmembers alike.

Chad Pomeroy, a law professor at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, wrote a 2019 article decrying a lack of financial transparency required of the church, given its tax-exempt status as a religion and a relative lack of financial reporting for all churches in the U.S.

When guessing about total LDS Church wealth, the scholar said, “some people call it ‘wild speculation.’”

“I don’t know if it’s wild, but it is speculative,” said Pomeroy, who graduated from BYU’s law school, “because we don’t get the information we’re asking for — even though, in effect, the U.S. taxpayer is underwriting the accumulation of this wealth.”

Irrespective of the shock value of dollar totals involved, he added, “what’s jarring to me is that you have a tax-exempt entity that’s allowed to aggregate this amount of assets without telling anybody what they’ve got.”

Why this wealth fits the Mormon model

(Jeremy Harmon | The Salt Lake Tribune) The Philadelphia Pennsylvania Temple is seen in the distance behind a new housing development built by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 2016.

The notion of owning land as a financial safeguard against devastation, both personally and at a community level, has remained deeply embedded in Mormon culture almost since the faith’s 1830 founding.

While Latter-day Saints make up only about 1 of every 100 Americans, their church has built business holdings from near bankruptcy in the 1960s to rival those of some of the largest and wealthiest institutions in the world.

Real estate — prized alongside entrepreneurialism by church leaders as a means of expansion since the days of early founder Joseph Smith and pioneer-prophet Brigham Young — has now blossomed into a multibillion-dollar affair, spanning continents.

Truth & Transparency Foundation’s release comes on the heels of other revelations regarding the faith’s finances, including assertions in late 2019 by a former church investment manager that its reserves topped $100 billion.

That portfolio, managed by Ensign Peak Advisors, the church’s investment arm, is currently reporting in federal filings a stock account above $52 billion.

Church leaders have said the reserves are a “rainy day” fund to help support global operations and guard against credit crunches, stock slides and recessions.

This land portfolio would represent about a third of what’s in Ensign Peak, which is only part of the church’s investment holdings. McKnight and others believe even the market values in the database are low estimates and that U.S. church lands could be as high as $25 billion to $30 billion in value.

In fact, Truth & Transparency believes its findings suggest the church has the most valuable private real estate portfolio in the U.S.

For all the church’s documented U.S. land wealth, scholarly research shows the denomination owns and manages large reserves of land in Britain — of a size rivaling the royal estate — along with massive acreages in Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina and Australia.

USU’s Mason said investing in land fits the church’s conservative buy-and-hold values in protecting its investments — born of the church’s financial difficulties in the 1950s and ‘60s.

“I know nothing about real estate development, except that they aren’t making any more land,” he said. “This seems very much like they are planning. They’re not just thinking about next year or five years from now. They’re thinking about 50 years from now.”

(Leah Hogsten | The Salt Lake Tribune) A new office skyscraper, with a meetinghouse in the lower levels, located at 95 State St. is nearing completion, March 25, 2022.