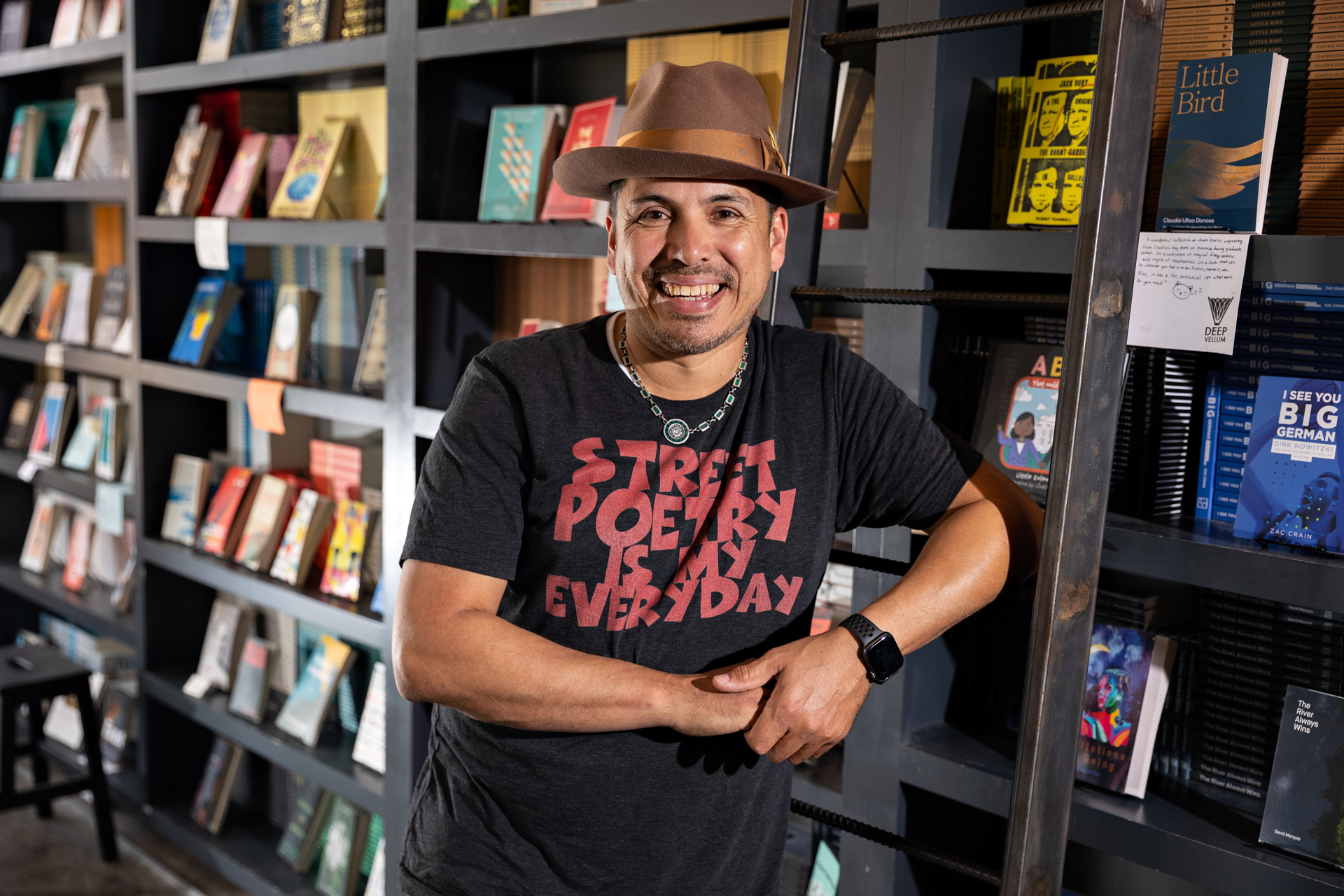

Joaquín Zihuatanejo. Photography by Shelby Tauber.

WHEN KIDS GO TO A PLAYGROUND in the summer, most of them aren’t thinking about how the metal slide might burn their skin or how the merry-go-round is rusty and structurally compromised.

They just play.

But when Joaquín Zihuatanejo went to the James B. Bonham Elementary playground with his friends, he considered his group daring for doing something potentially dangerous.

From a young age, Zihuatanejo wanted to be a poet. The first time his uncle asked him about his plans, he said he wanted to win a trophy, specifically the World Cup. One season on a soccer team quashed that dream.

He remembers his uncle telling him, “Maybe it’ll be books for you, mijo. Maybe it won’t be your feet that get you out of this neighborhood. Maybe it’ll be your mind and your words.”

When he was around 8 or 9 years old, Zihuatanejo read to his grandfather at night. He wanted to be out with friends, “causing trouble,” but instead he was at the house at the corner of Henderson and Belmont, reading selections from the Bible — or his grandfather’s favorite, the Norton Anthology of Poetry. To be rebellious, he wouldn’t put effort into his recitations.

“Mijo, if you don’t breathe life into it with your voice, how can I breathe life into it with my mind?” his grandfather would ask.

He was supposed to attend J.L. Long Middle School but ended up at Alex W. Spence Talented and Gifted Academy on a recommendation from someone at Dallas ISD. Then he attended Woodrow Wilson High School, an “awkward” and “shy” student and contributor to the literary magazine. From there it was off to the University of North Texas; then he taught English to high school students in Denton for seven years.

Zihuatanejo then wrote his first book, Barrio Songs. He planned to use a year to go on a speaking tour and host writing workshops, then return to the classroom. But one gig led to another, one year became two, and Zihuatanejo never went back to his teaching job.

“Every year on my taxes — at the bottom of the form you write your job title — the last 14 years, I’ve been writing the word ‘poet,’” he says. “And I feel ridiculously lucky to be able to do that.”

Eventually Zihuatanejo, who’s 51, discovered slam poetry. He became the national champion and then the world champion. He founded Dallas Youth Poets, an organization that trains and takes local, young poets to the Brave New Voices competition. He authored seven books and most recently, was named Dallas’ first-ever poet laureate.

WHAT DO YOU THINK IS THE IMPORTANCE OF POETRY?

I think the world is desperate for poetry now more than it ever has been. I think it’s because of the underlying single, central significance of it. That is this: poetry is one of those very rare and precious things, and every time you experience it, in its truest and most extraordinary form, it connects you to the shared humanity that binds us.

WHAT IS YOUR WRITING PROCESS LIKE?

I feel very lucky that I find myself in a situation now where I’m actually able to give myself a writing schedule. I tend to give myself like four hours in the mornings to write. And I try to do this five days a week. And sometimes I’ll sit and it’s just, it’s generative. And it’s like, I don’t even know where it’s coming from. It’s just all happening so fluidly. And other times I sit in silence for hours, waiting for the words to come. But I usually won’t wait for hours. If it’s not coming within the first half hour, and I’m struggling, I’ll simply read, or I’ll research, thinking about what I’m writing about. Sometimes when you research a particular image, there’s an entire vocabulary associated with that image, filled with extraordinary words that you might not have thought about using in the poem until you did the work.

WHAT ARE SOME REASONS WHY YOU WRITE?

I think I write because I have to, first and foremost. I go to bed thinking about writing. I wake up anxious to write, to be around words. And I am sure that people feel the same way about auto mechanics or about law or about teaching. I have to write. I think another reason I write is because someone has to check people. Maybe part of my job is to check those who seek to do harm to others. I can’t use my fists; it’s wrong. But I can use my words. I can use the line. I can use the page.

TALK ABOUT YOUR EXPERIENCE WITH SLAM POETRY.

The first thing that popped up when I typed in “how do I be a poet in Dallas,” was the Dallas Poetry Slam. And I walked into that place, and I was just blown away with how cool it was. I didn’t think I was cool enough for it. I was a high school English teacher at the time. And it was alive. It was like a beautiful dance, with the audience leaning in and the poet leaning in. It was like nothing I’ve ever seen. It instantly became my thing. I was like, I’m not sure where this is going to take me. But I want to be connected to this in a very real way.

WHAT DO YOU WANT TO ACCOMPLISH AS POET LAUREATE?

I want to be one of the few people of Dallas who set foot in every library that we have. But I want to facilitate there. I want to teach a workshop and maybe even offer a reading and a Q&A at every branch, because I think poetry belongs in every community. And then I piggybacked off that with, there are certain schools in Dallas that are, you think of Dallas, you think of that school. For me, Woodrow is one of those schools. I want to visit as many schools as I can to share my story of what it is to go from the barrio boy of East Dallas to world champion and see if I can inspire young people to write as well. I want to create ways for our city to stumble upon poetry, like accidentally run into a poem, be it a sign on a city bus, or maybe something at a park. But I don’t want it to be poems from the cannon; I want it to be poems by poets who live in Dallas. Another initiative that I’m really excited about, and the library’s behind me all the way on this is, poets who live in the city of Dallas, I want to offer them open office hours during my two years — meaning a poet age 8 to 80 can come to the Central Library and sit with me for 30 minutes, 45 minutes or an hour. And we can workshop a poem together.