They gave her a metal spoon. It was the first mistake her guards made. It would prove to be just enough to set her free.

For more than 40 days, Sara Miran had been held hostage by an Iranian-backed militia that operated with almost total impunity in post-Saddam Iraq. Miran, a real estate developer who lived in Virginia, was kidnapped while she was working in Iraq in September 2014. She was imprisoned in a locked, third-floor room of a house in a Baghdad neighborhood that served as one of the militia’s strongholds. The room had wood paneling and a marble floor; this had once been an elegant home, transformed into the militia’s prison.

Miran was certain the militia was going to kill her. Her captors forced her to wear a prison uniform, like the clothes the Islamic State group made its hostages wear just before they were executed. They had whipped her for five straight days with wire cables, trying to make her falsely confess to being a CIA spy. Her guards never showed their faces, and when she asked why, one of them said they would reveal themselves when she was about to be released. “Once I heard him say that, I knew they were going to kill me,” Miran told The Intercept. She knew they would never let her go if she could identify them.

She was desperate to escape. There were at least two guards in the house at all times, and they searched her room each day to make certain that she wasn’t plotting a breakout. They installed a surveillance camera in the room so they could monitor her movements 24 hours a day, watching even while she slept on a mattress on the floor.

Her captors fed her the bare minimum to keep her alive — a half piece of bread, some cheese, tea, a little soup — and she lost 30 pounds. With each meal, they brought her plastic spoons. But on a Sunday in October, her guards altered their routine. Instead of bread and cheese, they brought her a lunch of rice and curry. And along with the new meal came a metal spoon.

Miran hid the spoon in the tank of the toilet in the bathroom adjoining her room. Then she waited for the night.

At 9 p.m., she went into the bathroom and got the spoon. With years of experience as a manager of construction projects, she knew the weak points in building designs, and so she used the spoon to dig into the edges of the wall surrounding the small bathroom window. It took her 15 minutes to remove the frame and the window without breaking the glass. She said a silent prayer of thanks that the guards had not heard the noise she had made.

She went to her room’s closet and put on the clothes she had been wearing when she had been kidnapped, which her captors had incongruously left with her. She then put on her maroon prison uniform, topped with a hijab, so she wouldn’t rip her own clothes while escaping. Back in the bathroom, she leaned a chair against the wall and looked out the window. She was three stories aboveground, on the back side of the house. At 10 p.m., she squeezed through the window, grabbed onto a drain pipe anchored to the side of the house, and began to climb down. There was no turning back.

Left/Top: Sara Miran’s side table containing beauty products, a jewelry box, and three handguns belonging to her, her husband, and her security guard. Right/Bottom: A view from Sara Miran’s apartment complex in the Green Zone in Baghdad, Iraq, in 2022. Photos: Emily Garthwaite for The Intercept

Sara Miran’s story is the remarkable answer to what seemed for years to be an unsolvable human mystery, one that was buried deep in an archive of secret Iranian documents that were leaked to The Intercept.

When The Intercept published a series of stories in 2019 based on an archive of hundreds of leaked Iranian intelligence cables detailing how Iraq had fallen under the sway of Iran, one document contained what appeared to be a fragmentary clue to an untold story. The document was a report of a 2014 meeting between an Iraqi official and the Iranian consul in the southern Iraqi city of Basra.

“The subject of the meeting was Ms. Sara,” stated the cable, which was written by an Iranian intelligence officer and sent to Iranian intelligence headquarters in Tehran. The Iraqi official told the Iranian counsel that he was relaying a message from officials in Kurdistan, the semi-autonomous region in northern Iraq. The Kurdish officials wanted to get a message to Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani, the powerful head of Iran’s Quds Force — the secretive intelligence and special operations arm of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps that dominated Iraq — to release “Sara,” a woman who had apparently been kidnapped in Basra.

After the meeting, the Iranian consul gathered the intelligence officers who worked in his consulate. He wanted to know from them what was really going on. Why did the Kurds care so much about this woman named Sara? Why did they want to get a message to Suleimani about her? Above all, he wanted to know the answer to this simple question: What do we know about Sara?

The intelligence cable did not include the answers. It didn’t even include Sara’s last name, or her nationality. And so the mystery of “Sara” lingered, long after The Intercept published other stories based on the Iranian documents.

It took time to unlock the story. Clues in the archive of leaked cables helped, but ultimately it came down to old-fashioned reporting, phone calls during the Covid-19 pandemic to a wide variety of people in Basra, Baghdad, and Kurdistan, which finally led to a name: Sara Miran. Another round of reporting led to Miran herself, and to extensive interviews with her and members of her family, along with business associates, government officials, and others familiar with the case. Key elements of her story were also confirmed by documents subsequently obtained by The Intercept.

Once unearthed, Sara Miran’s story turned out to be a remarkable tale of an ambitious Kurdish American businesswoman whose kidnapping, and her efforts to escape and survive, ultimately led to a nighttime battle through the streets of Baghdad between the heavily armed Iranian-backed militia that kidnapped her and the Iraqi federal police and the Iraqi presidential guard force seeking to rescue her. It was a running gunfight, evocative of an action movie, involving hundreds of combatants from opposite ends of Iraq’s sectarian divide, all battling over a woman who lived in an American suburb.

On a human level, Miran’s story is an anatomy of a kidnapping, an underreported scourge on unstable countries like Iraq. Thousands of Iraqis and foreigners living and working in the country have been kidnapping victims since the U.S. invasion in 2003, many disappearing without a trace even after ransoms have been paid. Most kidnappings in Iraq are conducted by militias and criminal gangs for money, but Miran’s kidnapping was one of the unusual cases that had both political and financial overtones. Miran is also one of the few high-profile kidnapping victims in Iraq to escape, survive, and tell her story.

“My kidnapping is something that has happened to many other people,” she told The Intercept. “Many of them were killed, and others can’t speak about what happened to them because of fear. They have killed many, many other people, and they remove their bodies and threaten their families if they talk about it. I believe that God was on my side.”

Photo: Emily Garthwaite for The Intercept

Sara Hameed Miran was born in 1977 into a politically connected family in Sulaymaniyah, in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq.

Her family’s wealth and influence couldn’t protect her from the bitter combat that raged almost nonstop during her childhood. Wars blurred together. There was the Iran-Iraq war, the Kurdish insurgency against the regime of Saddam Hussein, the Kurdish civil war between two powerful Kurdish factions, and the American wars against Iraq. “I was born into bombs and guns,” she says. Her experience with war hardened her in ways that she now believes helped her stand up to threats and survive her kidnapping. During an extensive series of interviews for this story, she matter-of-factly described in graphic detail the most intense episodes of her life and of her kidnapping ordeal.

One of her earliest memories is of watching a gunfight on the street that spilled into the driveway of her family’s home; she was only 3 or 4, and she’s not sure who the combatants were. When she was older, she saw how the Peshmerga, the Kurdish militia, would slip into Sulaymaniyah from the surrounding mountains at night to attack Saddam’s army; rocket fire would force Miran and her family to hide under the stairwell in their house. “Every month or two, my father would have to replace the windows on our house, because there were no windows left,” she recalls. By the time she was 14, she was able to handle an AK-47.

After Saddam’s grip on Kurdistan was weakened by his defeat in the 1991 Gulf War with America, the major Kurdish factions agreed to hold elections for a new Kurdish parliament, and Miran’s father was elected. She moved with the rest of her family to Erbil, the Kurdish regional capital, where her father took his seat in parliament. Her family maintained its real estate holdings and other business interests in Sulaymaniyah.

Miran finished high school and fell in love with Gring Marif, a neighbor. Their proposed wedding led to tensions with her parents, because she came from a much more prominent family. But she insisted, and they were married in 1998 and had two sons and a daughter. While it was an unhappy marriage, it would eventually bring Miran and her children to America.

In 2003, Miran graduated from Salahaddin University, where she studied engineering. That year, the United States invaded Iraq, and her husband went to work for the U.S. military as a translator, and later for the U.S.-backed Kurdish intelligence service. Miran briefly taught at Salahaddin University before going to work for a property development firm that had special political connections; one of its co-owners was Nechirvan Barzani, Kurdistan’s prime minister and a member of one of the most powerful families in the Kurdish region. Miran started as an office administrator, but by 2005 became the chief of engineering for the firm. By 2007, she was the firm’s project manager for a huge shopping mall development that had 5,000 construction workers. She was becoming one of the fastest-rising women in business in Iraq.

And that’s what led her to Basra.

Photo: AFP via Getty Images

In 2010, Barzani and Nizar al-Hana, the other owner of the real estate firm, put Miran in charge of one of their most difficult projects: the renovation of the Basra International Hotel. It was the largest hotel in a city that had been riven by years of insurgency and war after the fall of Baghdad. In the predominantly Shia region of southern Iraq, Basra was dominated by nearby Iran and Iranian-backed militias. Miran’s work there gave her a rough introduction to the kind of political and criminal forces that would be behind her kidnapping four years later.

The sudden appearance of a Kurdish woman running a major construction project in war-torn Basra apparently angered the Iranian-backed power structure there, which opposed having an outsider take control of such a lucrative development. In April 2010, Miran was visited by a representative of one of the Iranian-backed militias in the city. The representative, whom she was told was an assassin, demanded that she abandon the hotel project and leave Basra.

Miran refused and instead turned to a powerful relative, Maj. Gen. Hussein Ali Kamal, a Kurd who was then Iraq’s deputy interior minister in charge of intelligence. Miran says her relative agreed to provide security for her, arranging for three Iraqi Humvees to be placed in front of the hotel construction site to try to ward off attacks.

It wasn’t enough.

In June, an explosion ripped through the apartment where Miran was living on her own (her children and husband had stayed behind in Kurdistan). She wasn’t in the apartment at the time, but it was a clear message to leave Basra. “They put a bomb in her room,” recalled Nizar al-Hana, the co-owner of the property company, in an interview with The Intercept. “Really, it is not easy to do things in Iraq.”

Despite the bombing, Miran refused to leave town. Instead, she moved out of her damaged apartment and into the hotel full time, while her secretary bought her new clothes to replace what she had lost in the bombing. She scrambled to finish the hotel project in eight months. “That was the hardest job I ever had,” she recalled.

Photo: Emily Garthwaite for The Intercept

In 2012, Miran moved with her husband and children to the United States, because her husband qualified for family visas as a result of his work with the American military in Iraq. They eventually settled in the northern Virginia suburbs of Washington. Even though she had a green card, her marriage was in trouble, and she returned to Iraq to again work on real estate development projects, now as a business partner with her former boss, Nizar al-Hana. Her family stayed behind in Virginia.

In 2013, she made a fateful return to Basra.

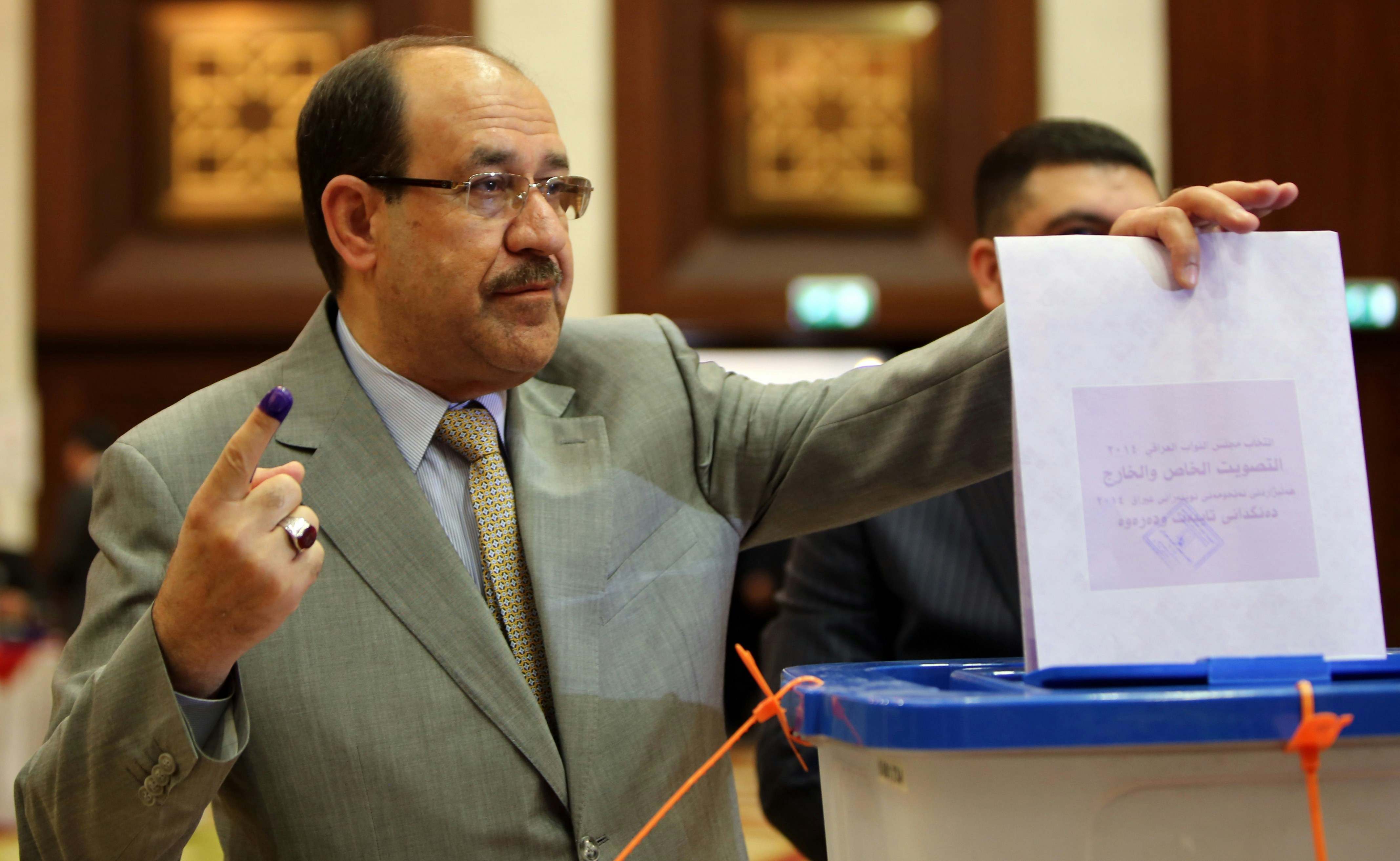

This time, Miran and her partner took on the construction of a massive residential development with more than 2,500 units of apartments and single-family homes. She obtained a large loan from a major Iraqi bank to finance the project. Word that Miran had obtained financing for her project — and was presumably flush with cash — quickly spread. In April 2014, she says, she came under pressure to siphon off $2 million from her bank loan for campaign funds for the party of Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. Parliamentary elections were scheduled to be held later that month, and Maliki and his party were scrambling to hold on to power.

After Miran refused, she says she received a series of threatening phone calls. In the first, she was told that if she continued to refuse to pay, she would get in “big trouble.” She said no. In the second, she was told that other business executives had paid, and she should too. She again said no. In yet another call, she was told that if she didn’t pay, she would be hurt. She said simply, “I will work on that problem when it comes to my doorstep.” She redoubled security at her construction site.

Hana, her business partner, told her to immediately leave Basra and return to Kurdistan. He believed that her courage in the face of such threats sometimes bordered on recklessness. “She’s crazy,” he joked.

Miran reluctantly took his advice, returning to Kurdistan in May before flying to the United States to see her family. But she returned to Basra to resume her work in September; she even brought her young daughter and a babysitter. It didn’t take long for trouble to find her.

She took up residence in the Basra hotel she had renovated a few years earlier, but the hotel’s chief of security soon warned her that an Iranian-backed militia was probably going to try to kidnap her. Miran says that the security chief offered to act as an intermediary with the militia and told her she could settle with the militia by paying $2 million. She refused but became more cautious about her movements around Basra. She rarely left the hotel. Even inside the hotel, she tried to hide from surveillance cameras, so that it would be harder for anyone to track her. “I knew where every camera was, I had them installed when I renovated the hotel,” she recalls.

It was too late. A powerful Iranian-backed militia, known as Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq — now designated as a foreign terrorist organization by the U.S. — was already watching her. On the morning of September 8, Miran drove to Basra’s provincial council building, the main office of the regional government, and met with two officials to discuss her construction project. When the meeting finished at about 11:50 a.m., she walked out of the building with her driver and another employee of her company.

Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki shows his ink-stained finger as he casts his vote in Iraq’s first parliamentary election since U.S. troops withdrew at a polling station in Baghdad’s Green Zone on April 30, 2014.

Photo: Ali Al-Saadi/AFP via Getty Images

Miran sensed something odd: The local police officers who normally stood guard outside the building’s main entrance were gone. She shook off her feeling of unease, walked about 20 yards down the street to where her white Lexus SUV was parked, got in the back seat, and began playing with her phone and shut out the world.

Her driver went about 30 yards before braking abruptly. Marin looked up and saw four vehicles blocking the road, while masked men in what looked like SWAT-type uniforms and carrying weapons walked toward her SUV. One of them pointed a handgun at her driver, and then a man with no mask, dressed in jeans and a white shirt, opened the back door next to her.

“Are you engineer Sara Hameed?” he asked, before dragging her out of the car while hurling insults at her and claiming, falsely, that he had an arrest warrant from Iraqi intelligence.

“He said, ‘You have a case against you from intelligence,’” Miran recalled. “I said I don’t have any problems with intelligence.”

He pointed a gun at her head and began dragging her down the street. She hit him in the stomach with her elbow, and he then hit her on the side of her face with the back of his handgun, leaving a deep bruise. She fell to the street, and then four men picked her up, threw her in the back of one of their vehicles, and then one of them tased her. “I pissed myself uncontrollably,” she recalls.

The men threw her face down on the floor in the back of the vehicle, covered her with a blanket, and climbed inside with her. The man in jeans and a white shirt stripped her of her expensive jewelry as they sped off.

Word of her kidnapping spread quickly to her family.

“On September 8, I got a phone call from an employee of the Basra project, and he said we heard your sister has been kidnapped, right in front of the provincial council’s building,” recalled Miran Beg, Sara’s brother.

Photo: Emily Garthwaite for The Intercept

The kidnappers drove her to a house about 90 miles from Basra on the road to Baghdad, where she spent her first night in captivity. The next morning, she was bound and gagged and stuffed into a hidden compartment in an SUV. On the drive, Miran could hear her kidnappers being waved through government checkpoints.

They took her to a house near Baghdad’s al-Sinek Bridge, the first of several houses where she was held in Iraq’s capital. She was kept there for just a few hours and was blindfolded, but she could hear that two men were also imprisoned there. Kidnapping was a big business for the militia.

Over the next few weeks, she was moved to different houses and interrogated, sometimes for hours in the middle of the night. Miran quickly realized how much her kidnappers already knew about her and her business operations. They knew, for instance, that she moved her firm’s money from Basra back to Kurdistan by having a trusted employee carry funds on a commercial flight from Basra to Erbil. They also knew she had tried to evade the surveillance cameras inside the hotel. And they told her that her daughter and babysitter had returned to Kurdistan. “They knew everything I was working on. It seemed like they had documents, they were flipping through notes and pages,” she told The Intercept.

Her kidnappers suspected she was an American spy; they couldn’t seem to imagine any other reason why a Kurdish woman with family in the United States would be working on a project in Basra. So they turned to torture. In a house in the Al Bayaa neighborhood of Baghdad, Miran was systematically beaten with wire cables, as her captors demanded that she confess that she worked for the CIA. Each day for five days, her captors restrained her with handcuffs on her arms and legs, lay her on the floor, and then a man wearing black clothes and a mask would whip her 10 times with the wire, slashing across her shoulders, back, hands, and legs. The beatings left her in such excruciating pain that even pouring water on her skin felt like torture.

She refused to give her kidnappers what they wanted. “I wasn’t going to confess to being a CIA agent when I’m not,” she said. “They had no common sense, they were idiots.”

She became despondent, convinced that she was about to be killed. She secretly wrote a note about herself on a small piece of paper, including her name and the date, stating that she had been kidnapped and that her captors claimed they had ties to Iraqi intelligence. (She did not yet know that her kidnappers were from Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq.) She hid the note in the wall of a bathroom in a house in Baghdad’s Sadr City, where she was held for about two weeks. If she didn’t survive, at least some record of her kidnapping might someday be discovered.

While Miran struggled to survive in captivity, her family’s wealth and political status in Kurdistan started to bring attention to her kidnapping. Her photograph was shown on Iraqi television news, and her kidnapping became a political issue in Kurdistan, where officials saw it as an affront to Kurdish sovereignty by Iranian-backed Shia forces. Her family used their network of political contacts to try to put pressure on government officials to help free Sara.

“We tried to contact all the people who we thought would have some power with the kidnappers — we tried to get help from a lot of people,” recalled Miran Beg, her brother. “When you have a family member kidnapped, you talk to a lot of people you never want to talk to.”

“When you have a family member kidnapped, you talk to a lot of people you never want to talk to.”

Hero Talibani — the wife of Jalal Talibani, a powerful Kurdish leader who had just stepped down as president of Iraq — took the opportunity at a reception in Baghdad to buttonhole Qassim Suleimani about the kidnapping. Hero Talibani later told Sara Miran that she had scolded Suleimani by saying “your militia has kidnapped her, give her back.” Suleimani insisted that “we don’t have Sara.” (Suleimani was killed in a U.S. air raid in Baghdad in 2020.).

Meanwhile, Masoud Barzani, the president of the Kurdistan autonomous region, wrote a letter to the provincial governor of Basra, demanding that he work to gain Miran’s release. The pressure from both the Talibani and Barzani families — the two most powerful families in Kurdistan — must have prompted the decision by the Basra governor to meet with the Iranian counsel in Basra. That is the meeting described in the Iranian intelligence cable leaked to The Intercept.

While Kurdish officials were applying pressure, Miran’s family received a ransom demand that immediately sounded like a scam. A member of the militia, apparently acting alone, phoned Miran’s brother, Miran Beg, and told him that he could free her in exchange for cash. “About a week after Sara’s kidnapping, I got a phone call from somebody, and he told me that he had information about Sara, and he wants me to give him $600,000,” recalled Miran Beg. “He told me I should come to Baghdad, and put $600,000 in an oil barrel used as a trash can. After that, Sara will be released. I said, let me talk to Sara and we can make a deal, and he said it’s not possible. Just come to Baghdad, put money in the barrel.”

Miran Beg contacted a senior Iraqi military commander who he knew and arranged for the cellphone number of the caller to be traced. The militia member was arrested at his Baghdad home. He was moved to Basra for questioning, but under enormous pressure from the militia’s political allies, the militia member was released.

After the freelance attempt to bilk Miran’s family, official ransom negotiations began between the kidnappers, Miran’s family, business associates, and Kurdish leaders. “I was negotiating with the kidnappers, they wanted me to pay them directly, and I refused, I said I’d pay a middle man,” recalls Nizar al-Hana, Miran’s business partner.

Kurdish President Masoud Barzani arranged for Zuhair al Garbawi, the chief of Iraqi intelligence, to act as an intermediary. Hana handed over $1 million to Garbawi to pay to the militia, but the kidnappers said it wasn’t enough; they demanded $2 million. Haggling led to a standoff. No ransom was paid, but negotiations continued.

Meanwhile, the kidnappers began to ask Miran detailed questions about her life. She realized that they had to provide answers to questions that only she would know, to prove to her family and others that she was still alive. But she also knew that if she answered the questions and a ransom was paid, the militia would kill her rather than release her. The only way to guarantee that she could stay alive was to make sure that no ransom money changed hands. She had to buy time until she could figure out how to escape, so she provided incorrect answers to all of the questions.

The ransom negotiations were still underway when her guards brought her the metal spoon.

Photo: Emily Garthwaite for The Intercept

When Miran climbed out the window and grabbed onto the drain pipe on the outside of the house where she was held captive, she found that she had to move slowly to maintain her balance and avoid falling. But after climbing down one story, she peered into the darkness and was able to see just how close she was to the roof of the neighboring two-story house. She jumped.

She made it onto the roof of the neighboring house, and then saw that she could make it onto the roof of the next house. She jumped again. She kept going, jumping from one roof to the next. Once she came to the sixth house, she stopped and looked down from the second story. She clambered down one story and jumped to the ground. Quickly looking around, she realized that she was in the walled-in backyard of a private home.

The noise from her fall alerted the people inside, and they immediately feared that thieves were trying to break in. Miran went to the back door, saw two women and a man inside, and asked them to open the door so she could leave their compound. They refused, and she then asked them to call the police. Instead, they went to get weapons, returning with a handgun and knives, and demanded to know why she had suddenly appeared in their back yard, loudly calling her a terrorist.

Miran tried to explain that she had been kidnapped, but the panicked homeowners refused to believe her and said they would contact the militia to check out her story. With a sinking feeling, Miran realized that the homeowners might turn her back over to her kidnappers. In desperation, she began scanning the yard to see if there was somewhere to hide. She crawled under a black tarp that covered an outdoor stove, while continuing to scream at the homeowners to call the police.

Finally recognizing that she was not an immediate threat, the homeowners called the federal police. When the police arrived, they searched Miran for weapons and bombs, and then brought her inside and asked her identity. She told a police captain who she was, and he was shocked; she had lost so much weight that he didn’t recognize her from the photos that had been shown on Iraqi television. “You don’t look like Sara at all,” the captain told her.

The captain called Miran’s husband, and he confirmed her identity. Realizing that he had discovered a famous kidnapping victim, the police captain brought Miran to his armored car, and while he reported to his superiors, he allowed her to sit in the vehicle and make calls to notify her relatives that she was free.

Even with the Iraqi federal police now on the scene, Sara Miran was still in danger. The raw power of the militia that had kidnapped her was about to reassert itself, leading to the surreal climax of the night.

Now seemingly safe inside the police’s armored car, Miran called her brother in Kurdistan.

“I took a call from an unknown number,” recalled Miran Beg. “I answered, and it was Sara. The time was 10:55 p.m. I said, ‘Where are you?’ She told me this is the number of the Iraqi federal police. She said, ‘I’m in the car of the police commander.’”

Miran Beg quickly spread the news to officials in both Baghdad and Kurdistan. Using another phone, he kept the line open with Sara while calling his contacts. One Kurdish official agreed to call Muhammad Fuad Masum, a Kurdish political leader who had just succeeded Jalal Talibani as president of Iraq.

Miran Beg also reached Lahur Talabany, the top counterterrorism and intelligence official in Kurdistan, who quickly arranged for the Iraqi presidential guard to be dispatched to the neighborhood where Sara had been found. Under the post-Saddam Iraqi political structure, Iraq’s president is always a Kurd, and so the presidential guard was the largest and most effective Kurdish-controlled security force in Baghdad. A total of 40 soldiers and four officers from the presidential guard were dispatched to the Karrada district where Miran was located, according to an official memo that was provided to The Intercept.

As the presidential guard sped across town, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq finally realized that one of its prized prisoners had escaped. Dozens of militia members soon gathered just down the street from where the federal police were sheltering Miran in the armored vehicle. The militia members began yelling at the police. “They were screaming, ‘Kill us!’” recalls Miran. “They were telling the police to kill us or give us Sara. They were saying she is CIA.”

Suddenly, automatic weapons fire ripped through the air. It’s not clear who fired first, but the showdown between Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq and the federal police quickly descended into a gun battle. During a lull, the militia called out to the police captain, who was just outside the armored vehicle, yelling that “we will do anything if you give her back,” according to Miran. The captain refused. The vehicle’s bulletproof armor was holding up under intense fire, but reinforcements were needed.

Miran’s brother had called Zuhair al Garbawi, the chief of Iraqi intelligence who had earlier agreed to be an intermediary in ransom negotiations in Miran’s case. Garbawi sent a group of armed intelligence officers to support the federal police. Yet they were still outnumbered, as more and more militia members poured onto the street.

Finally, the presidential troops arrived, with at least one heavy military vehicle, swinging the tide of the battle. As his forces deployed, the presidential guard commander saw that “the businesswoman Sarah Hameed Miran was inside a bulletproof/armored Landcruiser affiliated with the federal police,” according to the memo provided to The Intercept. Soon, the memo continued, “the armed militias (came) towards us, and they claimed that the kidnapped is a Jewish businesswoman affiliated with Israeli Mossad, and was plotting to destroy Iraq.” The militia members, armed with M4 assault rifles and M2 machine guns, “were speaking in Lebanese-accented Arabic,” the memo added. Iranian-backed militias in Iraq have close ties to Hezbollah, the Lebanese-based organization which is also backed by Iran.

The presidential guard joined the federal police in an intense firefight with the militia, leaving four federal police wounded and two militia members killed, according to the memo. The presidential force deployed a Russian-made BTR armored personnel carrier, enabling it to overpower the militia. They used the BTR to tow the armored car holding Miran away from the field of fire. Miran was transferred into the BTR and taken to federal police headquarters.

The showdown still wasn’t over.

Miran Beg said he contacted the chief of the federal police to warn him that the militia might attack the police building to get Sara back. At first the police official dismissed the threat, but a few minutes later, he called Miran Beg back. The militia had just threatened him. “What you said is true, take Sara away from my headquarters,” the police chief told Miran Beg. “They told me they will attack me with RPGs and heavy weapons.”

Under the protection of the presidential guard, Sara Miran was moved to the headquarters of Iraqi intelligence, where she was finally safe. Intelligence officials were eager to speak with her.

“The first question they asked me was, ‘What is the date today?’” recalled Miran. “And they asked me what time it was. By then it was 2 a.m. in the morning. I told them what day it was, and they said it was good that you are still functioning so well. I said I had been counting the days with my fingers and toes.”

She was then driven to the presidential palace, where she met with Masum, the new Iraqi president. She stayed at the palace for three days to recuperate. When the Iraqi Air Force offered a plane to fly her back to Kurdistan, Miran Beg asked that the chief of the Air Force fly with her. “That way they wouldn’t shoot the plane down,” he told The Intercept.

Miran received a VIP reception when she landed in Sulaymaniyah, where she was reunited with her family. A week later, they all flew back to the United States. The FBI met them at Dulles International Airport outside Washington, and took Miran and her family to their northern Virginia home. She agreed to a series of lengthy debriefings by the FBI, which wanted to better understand how militias like Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq conducted their kidnapping operations. U.S. officials confirmed that Miran was interviewed by the FBI about her kidnapping.

Photo: Courtesy of Sara Miran

Since her kidnapping, Miran and her husband divorced, and she has remarried. She and her family still live in northern Virginia, and she and her children are now U.S. citizens.

In 2016, Miran says that a local official in Basra texted her a photo of a diamond ring on his finger, the same diamond ring that she had been wearing when she was kidnapped, and which her kidnappers had taken from her. She says that the official relayed a message from Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, telling her that she could have the ring back, along with a promise of safety in Basra, if she paid the militia $1 million. She refused.

Undaunted, Miran has repeatedly traveled back to Basra since the kidnapping to complete her work on her residential development. “I had a lot of responsibility,” Miran said. “I didn’t have any assurances about going back, but I had to go back.” She added, “I have a gun on me to defend me.”

It may be useful. Earlier this month, while working on her project in Basra, she was warned by Kurdish intelligence of a new threat against her life from an Iranian-backed militia. Sara Miran is once again in danger.